by Piero Cammerinesi

It was the year 1973.

Two years had passed since I met my Master, since Massimo Scaligero entered my life.

I have spoken about this encounter in various interviews and more extensively in the film I dedicated to him, OLTRE, un Tributo a Massimo Scaligero (Beyond, a Tribute to Massimo Scaligero).

However, I have never spoken about what happened some time before and some time after that encounter.

Despite being very young, I desperately sought a spiritual reference point in the previous two years because a series of events in my personal life brought me into contact with the existence of a supersensible world. I understood this world to be the matrix of the external world in some way.

I sought this reference point in many ways: through Yoga and Zen, by using psychotropic substances, and by seeking a clear clue as to the direction to take in séances and with would-be Eastern masters.

For some time, I followed Jiddu Krishnamurti during the years when he gave lectures in Rome, either at the Pasquino or in a hotel on Via Cavour. He was certainly a fascinating personality, but he did not convince me completely.

I found myself at a dead end.

The summer before I met Massimo—my first encounter with him took place on April 12, 1971—I decided to actively search for the Master. I left without delay, hitchhiking alone with just pennies in my pocket, heading east. It was an intense and risky experience, though it was still possible to travel by hitchhiking safely at that time.

However, I was convinced by certain signs that I would find nothing in the direction I was looking. In Istanbul, in the summer of 1970, cholera broke out, and I fled Turkey in a hurry, leaving just a few hours before the border with Greece closed. Not to mention the unusual encounters I had and the risks I took during the journey. Those experiences alone would be enough to write an adventure story.

After a month away, I returned to Rome with a special amulet that I had found. It somehow reassured me that something would happen soon and that I would find what I was looking for.

During the occupation of my high school, J.F. Kennedy, a friend told me about a “strange” man who had a studio in an attic in Monteverde Vecchio, a district of Rome.

That November night, in the occupied high school, in front of a crackling fire, I suddenly realized two things.

First, everything we were looking for—our generation of revolts, political protests, and dissent—could be reduced to a demand for love. In 1968 and beyond, we believed we were making politics; we were searching for a political solution to the contradictions of the time.

But deep down, we were searching for love.

Even in the most heated political assemblies, when we gathered together, we were seeking contact with others; we were seeking the love of others.

This was the first realization that hit me with a clarity I had never experienced before.

What we saw on the outside was an illusion.

Or, as they say in the East, Maya.

The second thing I understood was that the external aids I had used, such as psychoactive substances and séances, did not offer any real access to the plane of reality I was seeking.

I remember returning to Turkey—this time with two friends and by plane—and on New Year’s Eve 1971, I committed to no longer using devious means to find what I was looking for.

It was then that I met the Master.

Less than four months later, the encounter was decisive—an immediate and dazzling recognition.

That was the before.

I must add another turning point as for after.

About two years had passed—during which weekly private meetings with Massimo were a gift and an experience of indescribable depth and happiness—when he asked me one day to start a group of people my age to begin spiritual work with.

He suggested working on Rudolf Steiner‘s The Philosophy of Freedom in the group..

He considered this Steiner work to be fundamental, and believed that it should be made known to the world.

At first, I hesitated and asked him if he was joking. After all, I was not yet twenty years old, and even though I had enrolled in the Faculty of Philosophy at the university, I did not feel capable of doing such a thing.

He smiled at me with his loving, indescribably deep gaze and said,

“Don’t worry; you will gain strength.”

I began a weekly study commitment with friends who, like me, saw the need for inner growth to understand the world behind the appearances of politics and social unrest.

***

More than fifty years have passed since then, and I have never stopped working on The Philosophy of Freedom, though I alternate it with other texts.

I consider this work to be the starting point for any serious exploration of the spiritual dimension.

I consider this work to be the starting point for any serious exploration of the spiritual dimension.

It is a living book that changes over time and speaks to us differently depending on our state of evolution.

As we know from experience, a book we read at twenty is not the same book we encounter again at forty or sixty.

Some books grow with us—or rather, they have a slow-release truth.

As Plato pointed out, every person can only remember the truth that already exists within them because everyone has contemplated the world of ideas before birth. This is why we do not recognize anything other than what we already have within us as truth.

This illustrates how challenging it is to convince individuals who refuse to acknowledge even the most evident truths when their preconceptions obstruct their ability to do so.

Thus, over the decades, this book has become, as Nietzsche would say, “flesh and blood”, transforming itself into a sort of operational tool for navigating life.

In the various groups and circles in which I had the pleasure and privilege of talking about this book, one recurring question has always been:

“How can I put the contents of The Philosophy of Freedom into practice?”

It is very important that this question arises because it aligns with the author’s intention for this work to always emphasize its practical aspect.

This Philosophy of Freedom was conceived in such a way that it is quite different from other philosophical books of the present time, which more or less aim by what is written to share something about how things are in the world or how they must be according to the ideas of the authors. However, this is not the immediate aim of this book. Rather, it is intended to give someone who engages with the thoughts presented there a kind of workout for his thoughts, so that the kind of thinking, the special way to devoting oneself to these thoughts is one in which the emotions and feelings of the soul are set in motion—just as in gymnastics the limbs are exercised, if I may use this comparison. What is otherwise only a method of gaining insight, is in this book at the same time a means of spiritual-soul self-education. This is extraordinarily important. (Rudolf Steiner, How Does One Attain Knowledge of the Spiritual World?, GA.60).

The author defines the work as a “means of spiritual-soul self-education.”

It is something to be used to both orient oneself in the outer world and proceed on the path to higher worlds.

It is a tool that can serve as a kind of “compass” in every area of our lives.

But how?

If there are three pillars of The Philosophy of Freedom—certainty of knowledge, the area of our freedom, and moral action—we can subject any event in the outer world to this cognitive-active process.

Only when I follow my love for the object is it I myself who acts. I act on this level of morality, not because I acknowledge a master over me, nor outer authority, nor a so-called inner voice. I acknowledge no outer principle for my actions: love for the action. I do not test intellectually, whether my action is good or evil; I carry it out because I love it. It will be “good” when my intuition, imbued with love, stands in the right way within the intuitively experienceable world configuration; “evil” when that is not the case. I also do not ask myself how another person would act in my position—but rather I act as I, this specific individuality, see myself moved to will. It is not what is generally done, the general custom, a general human maxim, a social norm, which leads me directly, but rather my love for the deed. I feel no compulsion, neither the compulsion of nature which leads me in the case of my drives, nor the compulsion of moral commandments, but rather I simply want to carry out what lives within me (Rudolf Steiner, Philosophy of Freedom, Chapter IX).

Consider, for example, the dramatic situation we are facing today: a world racing, seemingly without brakes, toward catastrophic war.

It is a world showing growing dehumanization in relations between institutions and populations, where the triumph of global lies is the “New Normal” in reporting facts.

If we are not insensitive or pathologically selfish, we won’t be able to avoid asking ourselves

“What can WE do?”

If we answer “nothing,” then we remain mere spectators, unaware of the meaning of events and of our own lives.

On the other hand, if we feel the moral impulse to act but lack a thorough understanding of reality, we risk doing something useless or making gross mistakes.

So, what should we do?

Let us try the method of the Philosophy of Freedom.

***

1) Certainty of knowledge.

First, Steiner asks whether there is a certain basis for knowledge in human activity. In the course of his book, he identifies this basis as thinking. The more independent our thinking is from our senses and instincts, the freer it will be, and the better we will understand ourselves and the world.

…within thinking and through thinking, he must come to know that element to which man seems to blind himself through the fact that he must interpose his life of mental pictures between the world and himself. (Rudolf Steiner, Philosophy of Freedom, Chapter V).

The goal is to use a philosophical approach to achieve an experience of sense-free thinking through soul observation.

Now, let’s apply this to our understanding of events around us.

What does that mean?

It’s simple. If I want to truly understand a situation—for example, the roots of the war in Ukraine or the horrors in Palestine—I must study history thoroughly with an open mind, free from my instinctive beliefs and prejudices. I must not limit myself to biased narratives but try to get to the root of the facts and the underlying causes of external events.

It is not necessary to be an expert or a historian because, as Rudolf Steiner repeatedly emphasizes in the aforementioned work, we are all capable of grasping an element of truth, however limited.

2) Area of freedom.

We will only be able to choose one interpretation or another when we have formed a fairly accurate idea of what can help us understand the unfolding events, completely free from any imposed narrative. This is because we will have arrived at the interpretation through a certain mode of knowing.

Inner freedom is impossible if something outside of me (a mechanical process or a merely inferred God outside the world) determines my moral mental pictures. I am therefore free only when I myself produce these mental pictures, not when I am able to carry out the stimuli to action which another being has instilled in me. A free being is one that can want what he himself considers to be right. Whoever does something other than he wants to, has to be driven to this other thing by motives which do not lie within him. Such a person acts unfreely. (Rudolf Steiner, Philosophy of Freedom, Chapter XII).

However, if our representations are influenced by the mainstream media narrative or that of so-called counter-information, which often presents the same biases, our lack of cognitive autonomy prevents us from being free.

We must therefore put truly autonomous thinking into practice.

For example, we can share what we have intuited with other people, we can write about it, we can act through demonstrations or petitions or contributions to suffering populations, and so on, but it is only thanks to this triad of certainty of knowledge-conquered freedom-morality in action that we can develop our moral action in the world.

Now you see why, in the year 1893, it became necessary for me to write the book The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, It is not the contents of this book that are so important, though obviously at that time one wished to tell the world what is said in it, but the most important thing is that independent thinking appeared in this book for the first time. No one can possibly understand this book who does not think independently. From the beginning, page by page, a reader must become accustomed to using his etheric body if he would think the thoughts in this book at all. Hence this book is a means of education—a very important means—and must be taken up as such. (Rudolf Steiner, Learning to See in the Spiritual World, GA 350).

Resuming the discourse, if we arrive at a credible representation of geopolitical events through study, deepening, comparison, reflection, and our inner intuition, then we are no longer determined by external factors, such as political views, official narratives, race, religion, and people. Instead, we are free to understand and act in relation to what surrounds us.

When faced with the oppression, horror, and inhumanity of what is happening in the world, it is natural to feel the need to do something.

If we are minimally moral beings, we find it difficult to simply undergo what is happening before our eyes.

However, we can only successfully contribute to the flow of world history if we are free from all external constraints.

3) Moral action.

Here, the freedom we have gained allows us to choose an action that is a moral action—moral imagination, as Rudolf Steiner calls it—which can be expressed through our actions within our intervention area.

I acknowledge no outer principle for my actions: love for the action. I do not test intellectually, whether my action is good or evil; I carry it out because I love it. It will be “good” when my intuition, imbued with love, stands in the right way within the intuitively experienceable world configuration; “evil” when that is not the case. I also do not ask myself how another person would act in my position—but rather I act as I, this specific individuality, see myself moved to will. It is not what is generally done, the general custom, a general human maxim, a social norm, which leads me directly, but rather my love for the deed. I feel no compulsion, neither the compulsion of nature which leads me in the case of my drives, nor the compulsion of moral commandments, but rather I simply want to carry out what lives within me (Rudolf Steiner, Philosophy of Freedom, Chapter IX).

This obviously applies to every area of our existence, not only geopolitical events—to which we must still pay attention, since we are karmically involved in them—but also the personal sphere.

Consider, for instance, when people who are part of our lives suffer or make mistakes that we want to help them with.

In this case, too, the process is the same.

Don’t start from mere sentimentality, or the desire to help at all costs. Start from the certainty of knowledge. In other words, you want to gain an understanding of the critical issues or problems faced by individuals in their interactions with others and with destiny, based on a combination of knowledge and intuition.

Once we understand these elements, we can determine the area of freedom from which to take a stance, whether verbal or behavioral, to help the other person consciously.

Only through this freedom, gained through knowledge, can we hope to take morally correct and effective action for others.

Through this process, we can see that it is possible to radically transform our relationship with thinking, feeling, and acting.

To live in the love for one’s actions, and to let live in understanding for the other’s willing, is the basic maxim of free human beings. (Rudolf Steiner, Philosophy of Freedom, Chapter IX).

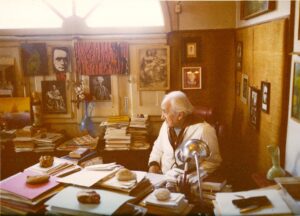

Cover image: Sandro Parise, Charon becomes Christopher after the turning point of time